The population in the US makes up a little over 4% of the world’s population. This 4% of the world’s population accounts for approximately 42% of worldwide pharmaceutical revenues. (1) The US accounted for over 64% of the sales of new drugs introduced between 2012 and 2017. (2) People in the US pay more for many brand-name prescription drugs than people in other countries for the same drugs. The price-discrimination issue in the US ranges from obscure drugs to America’s top-selling drug.

Turing Pharmaceuticals—The Extreme Example

Some blame the pharmaceutical manufacturers for raising prices. EpiPen’s distributor, Mylan, was in the news and in front of Congress when the company increased the price by approximately 500% over a seven-year period. As bad as the press was on Mylan, it pales in comparison to the scandalous pricing scheme from Turing Pharmaceuticals. Martin Shkreli, Turing’s CEO, received harsh news and congressional criticism for raising the price of Daraprim from $13.50 to $750.00 per pill. Daraprim is the brand name for pyrimethamine, which first came to the market in 1953. It is used as an antiparasitic and is on the World Health Organization’s “Essential Medicines” list. The parasitic condition can be considered fatal without the treatment, which typically requires a ninety-day supply. Shkreli became known as the world’s most-hated man and as “Pharma Bro” after he disrespected a congressional hearing by tweeting the word “imbeciles” afterward.

Despite the negative press and congressional pressure, Turing has kept the price inflated for a drug that has been on the market for over sixty-five years and is available as a generic in many other countries. The best price for a ninety-day supply of Daraprim in my sample city of Waukee, Iowa, on March 15, 2019, was $66,427.75 at Hy-Vee, and the highest price was $70,073 at a nearby Walgreens. Walgreens’ price was actually above the $750-per-pill list price! Shopping around could save a couple of thousand dollars, but the price for the required ninety-day supply is still significant. As previously mentioned, it is a life-saving drug, so maybe $70,000 is worth it. After all, insurance will pick up most of the cost. Remember, Turing has no research-and-development investment in this decades-old medication; it simply has the ability to charge whatever it wants or whatever the market will bear. If you need this particular antiparasitic, then maybe the price sounds acceptable to you.

Pyrimethamine is widely available throughout the world. I checked price and availability from an online pharmacy in India, which had sixty-nine different versions of pyrimethamine available. The first on the list cost $5.04 when converted to US dollars. The $5.04 is not per pill but for the full ninety-day supply. (3)

How can US pharmacies charge $70,073 for a drug that is available elsewhere for $5.04? They can do it because the US does not allow drug reimportation and does not allow the federal government to negotiate drug prices. States such as Maine have attempted to legalize reimportation to reduce the cost of drugs for its citizens, but the federal government has shut down these state-based initiatives.

Humira, The Biggest Example

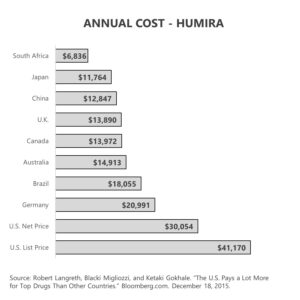

Prices for many brand-name drugs are higher in the US than in other countries. America’s highest-grossing drug is Humira. The 2018 sales in the US for Humira were $13.6 billion and were more than double the second leading drug’s revenue. (4) Humira is significantly more expensive in the US than in other countries.

Are these discriminatory drug-pricing problems the fault of the government, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), the pharmacy, the health plan, or the consumer? Maybe our high pharmaceutical cost has enough blame to pass around?

Federal Government

Many voters are starting to ask whether it is the federal government’s fault for allowing the pharmaceutical system to discriminate against American consumers. Unlike other countries, the US has no centralized government entity that negotiates and sets drug prices. In fact, other than in the US Department of Veterans Affairs and the US Department of Defense, the federal government is prohibited from negotiating drug prices even for public programs like Medicare.

To make matters even more difficult for the cost-conscious consumer, it is not legal to import pharmaceuticals from other countries, even though the same drug may be available for much less. Think about the pyrimethamine example, where the drug cost nearly $70,000 in the US and $5 in India.

President Trump committed to try fixing the drug-pricing problem through an aggressive executive order. “We’re working on a favored-nation clause, where we pay whatever the lowest nation’s price is,” said President Trump. (5) If this promise were to become a reality, it would dramatically lower drug prices for US consumers, but it would send economic shock waves through the pharmaceutical industry. President Trump’s plan lacked detail. He did not disclose when it would be effective, how it would be implemented, or who it would apply to. The statement likely goes the way of repeal-and-replace or build-the-wall; it is a forceful sound bite but not a likely reality. The bottom line is that President Trump is signaling that the pharmaceutical industry’s protections against government negotiation and drug reimportation are now on the negotiating table. Democratic presidential candidates are sending similar signals.

The pharmaceuticals industry is far and away the biggest investor in lobbying efforts in Washington, DC. (6) The pharma industry does not just have a voice in Washington, DC; it has the biggest voice. Ironically, the insurance industry holds second place in the “lobbying investment” category. Will the winner of the 2020 presidential election be able to speak louder?

Pharmacy Benefit Managers

Some blame PBMs for their spread pricing and rebate games. The difference between what the PBM buys and sells the drug for is known as spread. In addition to the pricing spread, there is a complex system of rebates that makes determining the real cost and value of a particular drug virtually impossible. PBMs are the middlemen in the pharmacy distribution channel. They sit between health plans, manufacturers, and pharmacies.

Some blame the potentially collusive merging of health insurers and PBMs. The three largest PBMs in the country are CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx.

- CVS, the owner of Caremark, completed its acquisition of Aetna in 2018, meaning the largest PBM now owns one of the largest health plans and is also one of the largest pharmacies. In essence, CVS negotiates the spread among all links in the supply chain.

- Express Scripts was the second-largest PBM and was acquired by Cigna in 2018.

- OptumRx is owned by United Healthcare.

The connection between pharmacy and health insurance could be an example of the fox watching the henhouse, or it could be the hens watching the fox den. Either way, health insurance and PBMs are inextricably linked in a massive game of vertical integration.

Consumers

There was a strong push toward the utilization of generic medications, a decision consumers ultimately make. A Commonwealth Fund study found that the US tied the UK for the highest use of generic drugs, at 84% of all scripts. This was more than double the rates for Australia and France. Consumers have appropriately played their part in generic drug substitution in the US, but our overall pharmacy cost is still high. (7)

New Zealand is the only other economically developed country that allows direct-to-consumer advertising for prescription drugs. In most countries, solely the physician determines which prescription should be prescribed. In the US, pharmaceutical manufacturers spend billions of dollars a year trying to persuade consumers to ask for their drug by name from their physician. Remember, none of these drugs are available without a prescription.

Is It a Price or a Ransom?

Disease can take you captive. It can disable you, cause intense pain, or even kill you. Disease is a criminal when it invades your body or your household. The insurance companies and the pharmaceutical companies are not the enemy . . . disease is. About a decade ago, an autoimmune disease known as Hashimoto’s took me captive. I was cold all the time, gaining weight, completely exhausted, mentally dazed, and my hair was falling out. When I finally went to see my physician after my symptoms became unbearable, my physician quickly diagnosed the problem. Hashimoto’s disease had attacked my thyroid and rendered it useless. Thankfully, I can manage the condition with a daily Levothyroxine pill that is available in generic form. I get my ninety-day supply at Walmart pharmacy for $10.00. If I take the drug, I feel fine and have no symptoms. If I were to elect to no longer take the medication, the condition would be fatal. My captor (Hashimoto’s disease) has taken me hostage with the threat of death, but thankfully, the ransom is only $10.00 every ninety days.

What if the ransom for the prescription was $10,000 every ninety days? What if it was $100,000 every ninety days? I would pay whatever copay was required, and I would hope and pray my insurance adequately covered the drug. I got lucky that my condition is cheap to cover, but people don’t get to choose their disease captors. When a disease takes you captive, you are much more of a hostage than a consumer; you will do whatever it takes to be set free. Maybe the federal government should consider managing the ransom demands? Pricing schemes that seem abusive to consumers could view the pharmaceutical industry rather than the disease as the kidnapping criminals.

What’s Next?

Should the federal government negotiate drug prices? Should the veiled world of spread pricing and rebates be brought into the light of day? Should the Food and Drug Administration start working on a plan to ensure the quality and safety of drugs imported from other countries? Should the price that Americans pay for prescription drugs be linked in some way to what people in other countries pay?

Prescription drug pricing will be a major campaign topic. Finding an answer that lowers cost while maintaining the level of quality control that Americans have come to expect and that adequately funds and rewards prescription drug breakthroughs is a monumental challenge facing Congress and the country. Lives and money are at stake.

Wow…lots of information covered there, and I’m not done yet. Next week, I’ll be taking a look at another big issue. The taxation of health insurance subsidies and premiums is inconsistent and discriminatory. Is that okay? Tune in to find out more. And, if you haven’t already, I encourage you to sign up for the “Insiders’ Club” where you’ll be notified when I release new information on my book “The Voter’s Guide to Healthcare: A non-partisan, candid, and relevant look at politics and healthcare in America.”

And great news…the book is also now available for sale on Amazon and Barnes and Noble. Check it out if you’re interested.

Sources

(1) International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations. “The Pharmaceutical Industry and Global Health. Facts and Figures 2017.” Ifpma.org. February 9, 2017.

(2) European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. “The Pharmaceutical Industry Facts and Figures, Key Data 2018.” Efpia.eu. 2018.

(3) “Generic Drugs (3065) with All Their Brand Names.” Medindia.com. February 2, 2017.

(4) Kyle Blankenship. “The Top 20 Drugs by 2018 US Sales.” Fierce Pharma. June 17, 2019.

(5) Kaiser Health News. “Trump Promises ‘Favored-Nation’ Plan to Try to Lower Drug Prices but Experts Say It Wouldn’t Move the Needle Much.” Khn.org. July 8, 2019.

(6) Center of Responsive Politics. Opensecrets.org

(7) Dana Sarnak, David Squires, and Shawn Bishop. “Paying for Prescription Drugs Around the World: Why Is the U.S. an Outlier?” Commonwealthfund.org. October 5, 2017.