Two patients are in hospital rooms right next to each other. They check in and out on the same days. They are seeing the same treating physician for the exact same procedure. The only real difference is that one is covered by Medicare and the other by private insurance. After discount, the hospital collects more than twice as much for the privately insured patient. Is this okay? If so, how much price discrimination is acceptable to you?

“Price discrimination is a pricing strategy that charges customers different prices for the same product or service. In pure price discrimination, the seller charges each customer the maximum price he or she will pay. In more common forms of price discrimination, the seller places customers in groups based on certain attributes and charges each group a different price.” (1) This is exactly how healthcare works. Hospitals group their customers according to the payment source: Medicare, Medicaid, uninsured, and commercially insured. This is known as payer mix. Profitability of a hospital system is often tied to effective management of this payer mix.

Payer mix matters so much in healthcare because the level of price discrimination is so high. Medicare does not negotiate with hospitals. Medicare reimburses based on its analysis of the cost of care, labor, real estate, etc., in a given geography for a specific procedure. Medicaid reimbursement strategies are set by each state and vary by state. Because Medicare, in contrast, is a consistent national platform, we will use Medicare as the baseline for this discussion.

Medicare Hospital-Reimbursement Methodology

Medicare uses its inpatient prospective payment system to set base reimbursement levels for inpatient services. The system determines the reimbursement by assigning one of over 700 diagnostic-related groups (DRGs) that adjust for patient age, gender, case complexity, comorbidity, and services. Medicare has been actively integrating value-based and quality factors into its reimbursements. The bottom line is that Medicare has a consistent national methodology for calculating healthcare service reimbursements based on its estimate of the efficient costs for delivering services. Medicare is a cost-based reimbursement system.

“The goal of Medicare payment policy is to get good value for the program’s expenditures, which means maintaining beneficiaries’ access to high-quality services while encouraging efficient use of resources. Anything less does not serve the interests of the taxpayers and beneficiaries who finance Medicare through their taxes and premiums.” (2) Medicare knows it puts patients’ access to medical providers at risk if its reimbursement levels fall too low.

In 2017, the aggregate hospital Medicare margin was –9.9%. (3) This means Medicare payments were less than the cost of providing the care. So, why wouldn’t hospitals just stop accepting Medicare patients since the reimbursement does not cover the cost? Hospitals still have an incentive to provide care to Medicare patients because the Medicare reimbursement helps cover fixed hospital costs and excess capacity. Average hospital occupancy was 62.5% in 2017. Medicare helps absorbs some of the cost of excess capacity in the US hospital system, even though Medicare is not profitable on a stand-alone basis.

Despite the under-reimbursement from public programs like Medicare and Medicaid, hospitals in the US have maintained their profit margins because of the commercial reimbursement rates. This overall profitability has risen and been maintained despite declining public-program reimbursement profitability because the gap between what the government pays for healthcare and what commercial insurance pays continues to widen.

How Big Is the Discrimination Spread?

Three independent data sources indicate that hospitals receive almost 250% of Medicare reimbursement rates from private insurance.

- Our company performed pricing analysis for a group of thirty-one cities in the Dallas–Fort Worth area. We found the most price-competitive networks were reimbursing hospitals at approximately 245% of Medicare for the total case mix of hospital services.

- The Rand Corporation studied hospital prices in twenty-five states in 2017 and found that privately insured patients paid 241% of what Medicare would have paid for the same procedures. (4)

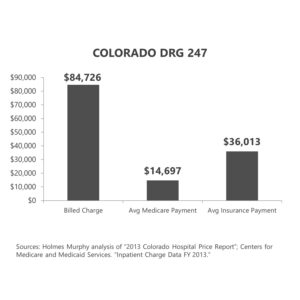

- A study of DRG 247—the code for the surgical procedure of placing a stent in an artery—in Colorado yielded similar results. The average billed charge was 576% of Medicare. The average commercial reimbursement after discount was 245% of Medicare.

Remember that the actual comparison to Medicare varies by hospital, procedure, geography, and specific network contract. What is consistent, however, is that commercial payers pay more than Medicare and Medicaid pay for identical services.

How Much Discrimination Is Okay?

Employers are starting to ask themselves how much price discrimination is okay. The State of North Carolina provides an interesting case study in the effort to link provider reimbursements to Medicare. (5) The state was facing a budget dilemma related to the health insurance plan for employees. The governor has authorized an annual budget increase of 4% per year for health insurance, but the health insurance costs have been rising at 5%–9% each year, so state treasurer Dale Folwell chaired a committee to evaluate options to keep the plan solvent. The three basic choices were (1) have the governor authorize bigger increases, (2) cut benefits or increase costs for plan participants, or (3) lower the cost of the plan. The governor was unwilling to increase taxes or cut other services to increase the funding, and the committee did not want to simply shift more cost to participants, so Treasurer Folwell and his committee created the Clear Pricing Project.

The Clear Pricing Project was a shift from traditional discount-payment methods to a reference-based system that linked what the state paid for healthcare services to what Medicare paid. The initial plan was to pay hospitals 160% of Medicare for inpatient services and 230% for outpatient services. The plan was vigorously opposed by most hospitals in the state. Deadlines came and went, and hospitals refused to sign up to treat state employees at the Medicare-indexed rates. The state increased reimbursements to gain hospital acceptance. In the end, only 5 hospitals in the entire state—and none of the state’s major hospital systems—agreed to the reimbursement that had grown to almost double the Medicare reimbursement rate. Treasurer Folwell said, “We’ve been exceedingly generous offering almost double what Medicare pays and yet not one large hospital would sign on—even those getting increases in pay. The fact is that transparent pricing terrifies them. Transparent pricing would end decades of secret contracts and high costs, causing them to have to actually compete for customers like any other business does in a free-market society.”

The lack of hospital participation caused the state to give up on the Clear Pricing Project. The state announced in August 2019 that the full Blue Cross Blue Shield network would be available for state employees.

Treasurer Folwell’s words indicate his frustration. Medical providers also expressed their frustration though the process. Frank Kauder, assistant director for Cone Health in Greensboro, North Carolina, sent an email to Treasurer Folwell that read, “Burn in hell, you sorry SOBs,” in response to the new reimbursement schedule. (6)

I do not believe that Mr. Kauder speaks for all hospital administrators. However, there is strong resistance to linking private insurance reimbursements to a Medicare-based formula, even if the formula guarantees a much higher reimbursement than Medicare. Presidential campaigns are actively promoting Medicare for all, which would pay all medical providers for all services the same Medicare rate. At the same time, the market is feuding over a cap that is almost double what Medicare pays. There is a massive gap between what politicians are promoting on the campaign trail and in debate halls compared to what the market is struggling to implement.

What About Transparency?

Congress and the Trump administration moved the transparency system one step further by requiring hospitals to make their chargemaster prices for services publicly available. (The chargemaster is the hospital’s retail price list.) The heart of this initiative was in the right place, but the coding complexity and sheer irrelevance of the gross billed charge hinders the effectiveness. What employers and consumers need to know is how much they will be charged after discounts, which typically exceed 50% for hospital services. The Trump administration is poking around the possibility of requiring medical providers to make their real prices—the ones negotiated between them and the networks—publicly available. America’s Health Insurance Plans, a lobbying association of large health insurance companies, is vehemently opposed to this level of transparency, claiming it would violate trade secrets. Maybe the problem with consumerism in healthcare is the fact that the real prices are veiled behind trade secrets!

Greater transparency in healthcare prices will not solve the discrimination problem, but it will lead to a greater demand for an indexed solution. Politicians should pay attention to this voter opportunity. Something’s got to give!

What’s Next?

Price discrimination is eating away at the earnings and savings for the 200 million Americans who don’t have government-sponsored healthcare, and that’s a lot of votes! Multiple bills in Washington, DC, are being circulated that would link the public and private reimbursement systems. The gap between what Medicare pays and what private insurance pays for healthcare services will decrease through either market-driven solutions or regulatory action.

Whew…that’s a lot of information to take in. But, I’m not done yet. Next week, I’ll be diving into health consumerism. What is it, what does it mean to you, and does it really work? And, if you haven’t already, I encourage you to sign up for the “Insiders’ Club” where you’ll be notified when I release new information AND receive a FREE copy of my book “The Voter’s Guide to Healthcare: A non-partisan, candid, and relevant look at politics and healthcare in America” when it’s available.

Sources

- Will Kenton. “Price Discrimination.” Investopedia.com. December 27, 2018.

- “Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy.” Medpac.gov. March 15, 2018.

- “Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy.” Medpac.gov. March 15, 2019.

- Chapin White and Christopher Whaley. “Prices Paid to Hospitals by Private Health Plans Are High Relative to Medicare and Vary Widely: Findings from an Employer-Led Transparency Initiative.” Rand.org. 2019.

- “North Carolina Health Plan Announces Network for 2020.” North Carolina Department of State Treasurer. Nctreasurer.com. August 8, 2019.

- Emily Rappleye. “‘Burn in Hell,’ Cone Health Manager Tells Health Plan via Email.” Becker’s Hospital Review. July 11, 2019.