Economist Milton Friedman is credited with saying, “Nobody spends somebody else’s money as wisely as he spends his own.” (1) The theory is that third-party reimbursement mechanisms, such as health insurance, create market and consumer inefficiency, leading to higher cost because the consumer is not the direct financial stakeholder. Republican healthcare platforms have embraced the Friedman theory of healthcare economics and almost always tout increased consumer responsibility as the cure for that which ails the healthcare system. The question is whether healthcare is truly an efficient consumer market where increased responsibility leads to lower cost and higher quality.

Consumer-driven healthcare plans (CDHPs) were envisioned in the late 1990s and launched around 2000. These plans were designed to pair greater financial exposure through high deductibles with web-based consumer tools. The consumer plans made the promise to lower cost and improve healthcare quality through empowered consumers. The landmark legislation for the healthcare consumer movement was the creation of the health savings account (HSA) in 2003. HSAs allow the employer and plan participant to put pretax money into an account to cover eligible healthcare expenses. The deposits can be invested to create a return that is also pretax. The HSA is the tax code triple play. Deposits are tax-free. Investment returns are tax-free. Reimbursements for eligible medical expenses are tax-free. The HSA is the only item in the Internal Revenue Code that allows for tax-free deposits, interest, and distributions.

Why doesn’t everyone have one of these tax-magic accounts? There is one hurdle that must be cleared to have an HSA: You must be enrolled in a qualified high-deductible health plan (HDHP). A qualified HDHP must have a deductible of at least $1,350 for single coverage and $2,700 for family coverage in 2019. In addition, coverage for treatment of an illness, injury, or condition must be subject to the deductible. Only preventive care can be reimbursed prior to meeting the deductible. This means no fixed-dollar co-pays prior to the deductible for office visits, nonpreventive prescription drugs, or routine care.

The term high-deductible health plan was not created by a marketing genius. Quite frankly, it doesn’t even sound appealing. This is what you get with your HDHP: higher up-front expenses for healthcare, exposure to significant healthcare pricing variability, increased responsibility for personal health, and greater awareness of the Internal Revenue Code. It doesn’t sound too appealing when you think of it that way. What the Republicans and the health insurance industry failed to recognize is the risk-averse mind-set of the American people.

Many people will overpay for additional predictability in health insurance. This buying mind-set and habit are not limited to health insurance. A 2004 Business Week study of Best Buy and Circuit City revealed that extended-warranty sales equaled 45% of Best Buy’s operating profits and 100% of the operating profits at Circuit City. The profit margin on these warranties was estimated to be eighteen times higher than the margin on the goods themselves. (2) Best Buy and Circuit City understood that American consumers were willing to pay, and pay a lot, for protection against financial unpredictability. When they designed consumer-directed high-deductible plans, Republicans and health insurance executives missed what electronics retailers understood.

Participant financial exposure to increased deductibles has skyrocketed over the past decade. The increased deductibles are not limited to HDHPs but apply to all types of insurance. The average deductible was almost 2.7 times higher in 2018 than it was in 2006.

In spite of their higher out-of-pocket exposure, CDHPs have found a firm foothold in the market. Fifty-eight percent (58%) of employers offer—and 29% of participants in employer-sponsored health plans choose—a CDHP. (3) The lower premium price is attractive to both employers and individual plan participants.

The promise of the CDHP movement was not only that these plans would lower premiums by shifting to higher deductibles but also that the increased consumerism would lower inflation. Think of it like flying a plane: The altimeter measures how high you are, and the trajectory indicates where you are going. High-deductible plans lower the altitude of the health-plan cost by shifting more of the healthcare expenses to the participant. This gap holds reasonably steady over time. HDHPs cost $645 less per year than other plans in 2007, and they cost $618 less per year in 2018.

Unfortunately, CDHPs have failed in their attempt to lower the trajectory of healthcare inflation. The promise of CDHPs was to provide not just a lower cost but also a lower rate of increase over time because of better consumer behaviors. This promise has not been fulfilled and has turned into modern-day snake oil. The Kaiser Family Foundation Employer Health Benefits Survey shows that HDHPs produced a higher rate of inflation than the other types of health insurance from 2007 to 2018; the plans designed to shift costs to employees to slow inflation have demonstrated the highest rates of inflation.

Rise of the Underinsured

The dramatic increase in deductibles and related out-of-pocket exposure has caused a dramatic increase in the number of underinsured Americans. My simple definition of underinsured is the situation in which a person has health insurance but cannot afford the plan’s deductibles and out-of-pocket expenditures if they have to use the insurance. In other words, they have health insurance but can’t afford to use it. Underinsurance can create a very negative set of consequences:

- bad debt for hospitals and physicians,

- drops in personal credit ratings,

- patients skipping needed health care services,

- patients not filling prescription drugs,

- collection agency pursuits,

- consumers incurring debt to pay medical bills, and

- consumer bankruptcy.

In 2018, seventy-one million Americans had problems paying a medical bill or had medical debt. (4) Sixty-five million American adults per year have a health issue but do not seek care because of concerns over cost, and Americans borrowed $88 billion in 2018 to fund out-of-pocket healthcare expenses. (5)

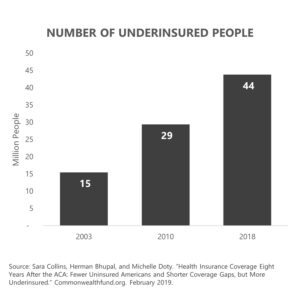

The Commonwealth Fund has a more formal definition of underinsurance than my street definition. Its definition includes adults who had health insurance for the entire year but had a deductible of 5% of income or more and incurred actual out-of-pocket expenses of 10% or more of income or 5% or more of income if below 200% of the FPL. These numbers exclude any premiums for which the individual is responsible. The number of Americans in this unaffordable situation almost tripled between 2003 and 2018.

The effort to get consumer “skin in the game” has created some deep financial wounds for millions of Americans.

What’s Next?

Does all of this prove that consumer-driven healthcare is a failed Republican and insurance-industry idea? It proves healthcare is not a perfect consumer market. When the choice is relief from unbearable pain—to take the medication or have a procedure that promises relief—what are you going to do? You are going to try what the doctor suggests. What do you do when you are told your child has a rare form of cancer and needs to travel to a specialist halfway across the country? You get on a plane to see the specialist, and you worry about how to pay for it later. The majority of healthcare treatments are for routine care, but the majority of expenses are not related to optional or discretionary treatments. The majority of healthcare expenses are related to catastrophic episodes or to complications related to chronic medical conditions.

Increasing out-of-pocket exposure is a dangerous game of roulette when the patient can’t afford the treatment even with insurance. Lawmakers and insurance companies need to rethink how to better connect patients with the high-value treatments that give patients the best chances to get better. Insurance should connect patients and providers rather than put a financial wall between them.

Speaking of a “wall,” in my next blog I’ll be diving into the “pharmaceutical border wall.” People in the US pay more for many brand-name prescription drugs than people in other countries for the same drugs. Why? How do we stop this? Tune in to find out my thoughts. And, if you haven’t already, I encourage you to sign up for the “Insiders’ Club” where you’ll be notified when I release new information AND receive a FREE copy of my book “The Voter’s Guide to Healthcare: A non-partisan, candid, and relevant look at politics and healthcare in America” when it’s available.

Sources

- Milton Friedman. “Friedman on the Surplus.” Hoover Digest. April 30, 2001.

- “Guaranteed Profits.” Business Week. December 20, 2004.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. “Employer Health Benefits Survey 2018.” Kff.org. October 3, 2018.

- Sara Collins, Herman Bhupal, and Michelle Doty. “Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA: Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, but More Underinsured.” Commonwealthfund.org. February 2019.

- Tami Luhby. “Americans Borrow $88 Billion Annually to Pay for Health Care, Survey Finds.” CNN.com. April 2, 2019.