Whether Colorado voters decide to socialize healthcare financing in the state (ColoradoCare AKA Amendment 69) or maintain the current hybrid of public and private financing, the issue of discrimination in healthcare — and what to do about it — remains.

Price discrimination in healthcare is real, and it’s measurable. My questions deal with what level of price discrimination is acceptable, what level is unethical, what level might be illegal, and what role, if any, should the government play? So in this blog, the last in my ColoradoCare series, we’ll be taking a look at price discrimination. (P.S. To view my first three blogs on the topic, visit “ColoradoCare Part 1: The Basics”, “ColoradoCare Part 2: Why it will Pass”, and “ColoradoCare Part 3: Why it will Fail.”)

Price Discrimination in Healthcare

First, I need to define price discrimination. It’s the practice of charging different customers different prices for identical goods or services. It’s a common practice that’s accepted in many businesses and industries. Movie theaters charge less for a matinee show time, and airlines charge passengers on the same plane different prices based on when they purchased their tickets and how full the plane is. Many restaurants and stores will give a discount to seniors or to military customers. Price discrimination doesn’t necessarily mean malicious intent, but it does confirm a transparent difference.

The healthcare industry straddles a unique position in that it’s a private industry that provides a social service — remember that the purchase of health insurance is now required by federal law. As a social service, the question of the government’s role in socializing healthcare pricing is continuing to rise. The federal government must approve all rate increases within the Health Insurance Marketplace. Washington DC is abuzz with anger for the EpiPen price increases. Should Congress have any say in how much a pharmaceutical company charges for a drug?

The federal government mandates Medicare reimbursements. The passage of Amendment 69 would allow the 21-person panel to negotiate, or mandate, the prices of healthcare services in Colorado.

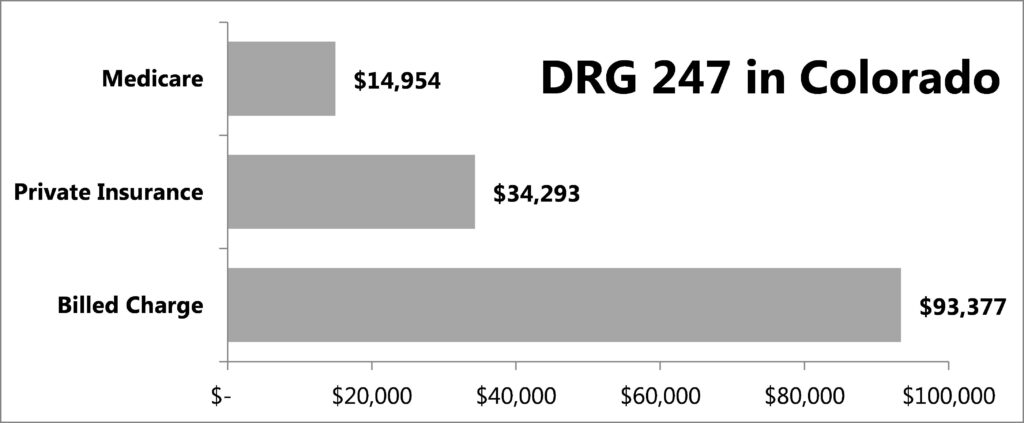

Price discrimination in healthcare is alive and well today in Colorado. I will use publicly available data for billed charges and reimbursement levels for a common procedure as an example:

- Diagnostic Related Group (DRG) 247 is for a cardiovascular stent. The average billed charge in 2014 in Colorado was $93,377.

- Montrose Memorial Hospital had the lowest average billed charge at $52,810.18.

- The North Suburban Medical Center in Thornton had the highest average billed rate of $160,508.95 for the exact same procedure.

Price variability is significant.

We all know that no one — or hardly any poor soul — would actually pay the billed charges. So how do actual paid reimbursements vary? Medicare reimbursed Colorado hospitals an average of $14,954 for DRG 247. Medicare bases its reimbursements on analysis of actual costs to deliver services. Private insurance (after negotiations and discounts) reimbursed an average of $34,293 for the exact same procedure.

There are two ways for Coloradans, and potentially the 21-person panel, to view this information. They could celebrate the 63 percent discount that managed care networks have achieved, or they could rage that they’re being charged over six times the Medicare reimbursement that’s based on actual cost of services or that they are actually paying 229 percent of the Medicare reimbursement. In other words, two people — one covered by Medicare and the other by private insurance — could enter the same hospital on the same day for the same procedure and one would pay almost $20,000 more.

This doesn’t really matter because insurance pays these claims…right? Health insurance is simply the financing mechanism for the cost of healthcare services. With Amendment 69, the procedure is directly funded with taxes and would state taxpayers be willing to pay more than double the amount that federal taxpayers pay?

The debate over the federal government’s role in healthcare didn’t end with the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The passage of the ACA signaled the start and not the end. Similarly, the debate over the government’s role in uncovering and potentially dealing with healthcare price discrimination in the state of Colorado won’t end with the passage or failure of Amendment 69…this is only the beginning.

So after this series, what are your thoughts? I’d like to see what questions, concerns, and thoughts you have. Let me know!

Want to read more about healthare prices? In this 2020 blog, Den Bishop does a deep dive into the harmaceutical border wall.